Book of Mormon Near Eastern Background |

Canaanite horned altar or incense burner from Megiddo in ancient Palestine (c. 1900 B.C.) in the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem. This distinctive style of altar was also used by the Israelites (see Lev. 4:7; 1 Kings 1:50, 2:28). Courtesy LaMar C. Berrett.

by Hugh W. Nibley

According to the Book of Mormon, the Jaredites, the Nephites, and the "Mulekites" (see Mulek) migrated to the Western Hemisphere from the Near East in antiquity, a claim that has been challenged. While Book of Mormon students readily admit that no direct, concrete evidence currently exists in substantiating the links with the ancient Near East that are noted in the book, evidence can be adduced—largely external and circumstantial—that commands respect for the claims of the Book of Mormon concerning its ancient Near Eastern background (CWHN 8:65-72). A few examples will indicate the nature and strength of these ties, particularly because such details were not available to Joseph Smith, the translator of the Book of Mormon, from any sources that existed in the early nineteenth century (see Book of Mormon Translation by Joseph Smith).

1. Lehi (c. 600 B.C.) was a righteous, wellborn, and prosperous man of the tribe of Manasseh who lived in or near Jerusalem. He traveled much, has a rich estate in the country, and had an eye for fine metalwork. His family was strongly influenced by the contemporary Egyptian culture. At a time of mounting tensions in Jerusalem (the officials were holding secret meetings by night), he favored the religious reform party of Jeremiah, while members of his family were torn by divided loyalties. One of many prophets of doom in the land, "a visionary man," he was forced to flee with his family, fearing pursuit by the troops of one Laban, a high military official of the city. Important records that Lehi needed were kept in the house of Laban (1 Ne. 1- 5; CWHN 6:46-131; 8:534-35). This closely parallels the situation in Lachish at the time, as described in contemporary records discovered in 1934-1935 (H. Torczyner, The Lachish Letters, 2 vols., Oxford, 1938; cf. CWHN 8:380-406). The Bar Kokhba letters, discovered in 1965-1966, recount the manner in which the wealthy escaped from Jerusalem under like circumstances in both earlier and later centuries (Y. Yadin, Bar Kokhba, Chaps, 10 and 16, Jerusalem, 1971; cf, CWHN 8:274-88).

2. Lehi's flight recalls the later retreat of the Desert Sectaries of the Dead Sea, both parties being bent on "keeping the commandments of the Lord" (cf. 1 Ne. 4:33-37; Battle Scroll [1QM] x. 7-8). Among the Desert Sectaries, all volunteers were sworn in by covenant (Battle Scroll [1QM] vii. 5-6). In the case of Nephi1, son of Lehi, he is charged with having "taken it upon him to be our ruler and our teacher…. He says that the Lord has talked with him…[to] lead us away into some strange wilderness" (1 Ne. 16:37-38). Later in the New World, Nephi, then Mosiah1, and then Alma1 (c. 150 B.C.) led out more devotees, for example, the last-named, to a place of trees by "the waters of Mormon" (2 Ne. 5:10-11; Omni 1:12-13; Mosiah 18). The organization and practices instigated by Alma are like those in the Old World communities: swearing in, baptism, one priest to fifty members, traveling teachers or inspectors, a special day for assembly, all labor and share alike, called "the children of God," all defer to one pre-eminent Teacher, and so on (Mosiah 18; 25). Parallels with the Dead Sea Scroll communities are striking, even to the rival Dead Sea colonies led by the False Teacher (CWHN 6:135-44, 157-67, 183-93; 7:264-70; 8:289-327).

3. "And my father dwelt in a tent" (1 Ne. 2:15). Mentioned fourteen times in 1 Nephi, the sheikh's tent is the center of everything. When Lehi's sons returned from Jerusalem safely after fleeing Laban's men and hiding in caves, "they did rejoice…and did offer sacrifices…on an alter of stones…and gave thanks" (1 Ne. 2:7; 5:9). Taking "seeds of every kind" for a protracted settlement, "keeping to the more fertile parts of the wilderness," they hunt along the way, making "not much fire," living on raw meat, guided at times by a "Liahona"—a brass ball "of curious workmanship" with two divination arrows that show the way. One long camping was "at a place we call Shazer" (cf. Arabic shajer, trees or place of trees); and they buried Ishmael at Nahom, where his daughters mourned and chided Lehi (1 Ne. 16; cf. Arabic Nahm, a moaning or sighing together, a chiding). Lehi vividly describes a sayl, a flash flood of "filthy water" out of a wadi or stream bed that can sweep one's camp away (1 Ne. 8:13,32; 12:16), a common event in the area where he was traveling. At their first "river of water" Lehi recited a formal "qasida," an old form of desert poetry, to his sons Laman and Lemuel, urgig them to be like the stream and the valley in keeping God's commands (1 Ne. 2). He describes the terror of those who in "a mist of darkness…did lose their way, wandered off and were lost." He sees "a great and spacious building," appearing to stand high "in the air…filled with people,…and their manner of dress was exceeding fine" (1 Ne. 8; cd. the "skyscrapers" of southern Arabia, e.g., the town of Shibam). The building fell in all its pride like the fabled Castle of Ghumdan. Other desert imagery abounds (CWHN 5:43-92).

4. Among lengthier connected accounts, Moroni1 (c. 75 B.C.), leading an uprising against an oppressor, "went forth among the people waving the rent part of his garment" to show the writing on it (Alma 46:19-20). The legendary Persian hero Kawe did the same thing with his garment. The men of Moroni "came running…. rending their garments…as a covenant [saying]…may [God] cast us at the feet of our enemies…to be trodden underfoot" (Alma 46:21-22). Both the rending of and the treading on the garments were ancient practices (CWHN 6:216-18; 7:198-202; 8:92-95). The inscription on the banner, "in memory of our God, our religion, and our peace, our wives, and our children" (Alma 46:12), is similar to the banners and trumpets of the armies in the Dead Sea Battle Scroll ([IQM] iii. 1-iv.2). Before the battle Moroni goes before the army and dedicates the land southward as Desolation, and the rest he named "a chosen land, and the land of liberty" (Alma 46:17). In the Battle Scroll ([1QM] vii.8ff.) the hight priest similarly goes before the army and dedicates the land of the enemy to destruction and that of Israel to salvation (CWHN 6:213-16). Moroni compmares his torn garment-banner to the coat of Joseph, half of which was preserved and half decayed: "Let us remember the words of Jacob, before his death…as this remnant of [the coat] hath been preserved, so shall a remnant of [Joseph] be preserved." So Jacob had both "sorrow…[and] joy" at the same time (Alma 46:24-25). An almost identical story is told by the tenth-century savant Tha'labi, the collector of traditions from Jewish refugees in Persia (CWHN 6:209-21; 8:249, 280-81).

5. There is a detailed description of a coronation in the Book of Mormon that is paraleled only in ancient nonbiblical sources, notable Nathan haBablil's description of the coronation of the Prince of the Captivity. The Book of Mormon version in Mosiah 2-6 (c. 125 B.C.) is a classic account of the well-documented ancient "Year Rite": (a) The people gather at the temple, (b) bringing firstfruits and offerings (Mosiah 2:3-4); (c) they camp by families, all tent doors facing the temple; (d) a special tower is erected, (e) from which the king addresses the people, (f) unfolding unto them "the mysteries" (the real ruler is God, etc.); (g) all accept the covenant in a great acclamation; (h) it is the universal birthday, all are reborn; (i) they receive a new name, are duly sealed, and registered in a nation cencus; (j) there is stirring choral music (cf. Mosiah 2:28; 5:2-5), (k) they feast by families (cf. Mosiah 2:5) and return to their homes (CWHN 6:205-310). This "patternism" has been recognized onlyy since the 1930s.

6. The literary evidence of Old World ties with the Book of Mormon is centered on Egyptian influences, requiring special treatment. The opening colophon to Nephi's autobiography in the Book of Mormon is characteristic: "I Nephi…I make it with mine own hand" (1 Ne. 1:1, 3). The characters of the original Book of Mormon writing most closely resemble Meroitic, a "reformed Egyptian" known from an Egyptian colony established on the upper Nile River in the same period (see Anthon Transcript; Book of Mormon Language). Proper names in the Book of Mormon include Ammon (the most common name in both 26th Dynasty Egypt [664-525 B.C.] and the Book of Mormon); Alma, which has long been derided for its usage as a man's name (now found in the Bar Kokhba letters as "Alma, son of Judah"); Aha, a Nephite general (cf. Egyptian aha, "warrior"); Paankhi (an important royal name of the Egyptian Late Period [525-332 B.C.]); Hermounts, a country of wild beasts (cf. Egyptian Hermonthis, God of wild places); Laman and Lemuel, "pendant names" commonly given to eldest sons (cf. Qabil and Habil, Harut and Marut); Lehi, a proper name (found on an ancient potshered in Ebion Gezer about 1938); Manti, a form of the Egyptian God Month; Korihor (cf. Egyptian Herhor, Horihor); and Giddianhi (cf. Egyptian Djhwti-ankhi, "Thoth is my life"), etc. (CWNH 5:25-34; 6:281-92; 7:149-52, 168-72; 8:281-82; see Book of Mormon Names).

7. The authenticity of the Gold Plates on which the Book of Mormon was inscribed has often been questioned until the finding of the Darius Plates in 1938. Many other examples of sacred and historical writing on metal plates have been found since (C. Wright in By Study and Also by Faith, 2:273-334, ed. J. Lundquist and S. Ricks, Salt Lake City, 1990). The brass (bronze) plates recall the Copper Scroll of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the metal being used to preserve particularly valuable information, namely the hiding places of treasures—scrolls, money, sacred utensils—concealed from the enemy. The Nephites were commanded, "They shall hide up their treasures…when they shall flee before their enemies," but if such treasures are used for private purposes thereafter, "because they will not hide them up unto [God], cursed be they and also their treasures" (Hel. 13:19-20; CWHN 5:105-107; 6:21-28: 7:56-57, 220-21, 272-74).

8. In sharp contrast to other cultures in the book, the Jaredites carried on the warring ways of the steppes of Asia "upon this north country" (Ether 1, 3- 6). Issuing forth from the well-known dispersion center of the great migrations in western Asia, they accepted all volunteers in a mass migration (Ether 1:41-42). Moving across central Asia they crossed shallow seas in barges (Ether 2:5-6). Such great inland seas were left over from the last ice age (CWHN 5:183-85, 194-96). Reaching the "great sea" (possibly the Pacific), they built ships with covered decks and peaked ends, "after the manner of Noah's ark" (Ether 6:7), closely resembling the prehistoric "magur boats" of Mesopotamia. The eight ships were lit by shining stones, as was Noah's ark according to the Palestinian Talmud, the stones mentioned in the Talmud and elsewhere being produced by a peculiar process described in ancient legends. Such arrangements were necessary because of "the furious wind…[that] did never cease to blow" (Ether 6:5, 8). In this connection, there are many ancient accounts of the "windflood"—tremendous winds sustained over a period of time—that followed the Flood and destroyed the Tower (CWHN 5:359-79; 6:329-34; 7:208-10).

9. The society of the Book of Ether is that of the "Epic Milieu" or "Heroic Age," a product of world upheaval and forced migrations (cf. descriptions in H. M. Chadwick, The Growth of Literature, 3 vols., Cambridge, 1932-1940). On the boundless plains loyalty must be secured by oaths, which are broken as individuals seek ever more power and gain. Kings' sons or brothers rebel to form new armies and empires, sometimes putting the king and his family under lifelong house arrest, while "drawing off" followers by gifts and lands in feudal fashion. Regal splendor is built on prison labor; there are plots and counterplots, feuds, and vendettas. War is played like a chess game with times and places set for battle and challenges by trumpet and messenger, all culminating in the personal duel of the rulers, winner take all. This makes for wars of extermination and total social breakdown with "every man with his band fighting for that which he desired" (Ether 7-15; CWHN 5:231-37, 285-307).

10. Elements of the archaic matriarchy were brought from the Old World by Book of Mormon Peoples (Ether 8:9-10). For instance, a Jaredite queen plots to put a young successor on the throne by teachery or a duel, and then supplants him with another, remaining in charge like the ancient perennial Great Mother in a royal court (cf. CWHN 5:210-13). The mother-goddess apparently turns up also among the Nephites in a cult-place (Siron), where the harlot Isabel and her associates were visited by crowds of devotees (Alma 39:3-4, 11); Isabel was the name of the great hierodule of the Phoenicians (CWHN 8:542).

(See Basic Beliefs home page; Scriptural Writings home page; The Book of Mormon home page)

Illustration

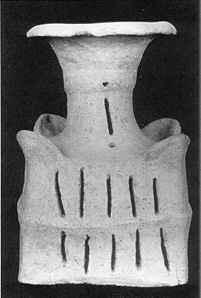

Similar to the horn altar from Israel is this four-cornered altar or incense burner from Oaxaca, Mexico, dating to the Monte Alban 1 period (c. 500-100 B.C.) Specimen in Museo-Frissell, Oaxaca, Mexico. Courtesy F.A.R.M.S.

Bibliography

Nibley, Hugh W. CWHN, Vols. 5-8. Salt Lake City, 1988-1989.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 1, Book of Mormon Near Eastern Background

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |