Social and Cultural History |

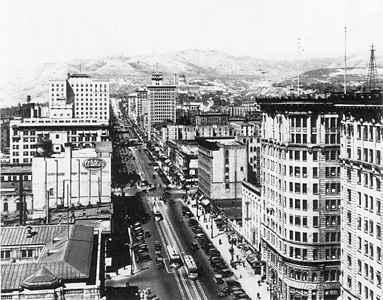

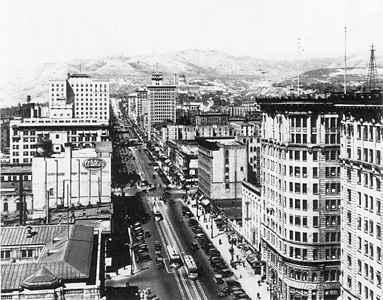

Salt Lake City Main Street, looking north from Fourth South Street (c. 1925). Photographer: Shiplers.

by Dean L. May

[For nineteenth-century beliefs and customs related more directly to worship, see Pioneer Life and Worship.]

As a people, members of THE CHURCH of JESUS CHRIST of Latter-day Saints have over time taken on distinctive qualities as their beliefs and historical experience have given shape and force to their society. Indeed, geographers speak frequently of a "Mormon Culture Region" covering all of Utah and extending into neighboring states, with identifiable traits that set it apart. Observers have long seen LDS social organization as more coherent and tightly knit than most societies in the United States.

Several forces have shaped LDS cultural and social life. Belief in the gathering motivated most early converts to migrate to areas where they could live with other Saints. Joseph Smith urged them, once gathered, to build homes in towns rather than on their farms, thus minimizing the physical distance between households and enhancing opportunities for social interaction (see City Planning). Joseph Smith founded programs to help build a more cohesive society and taught that cooperation was superior to individual enterprise. Priesthood power was extended to all the faithful, thus breaking down traditional class-based social hierarchies. The LDS belief that God inspired those acting in Church callings invested both local and general leaders with legitimacy at a time when authority in general was questioned widely among Americans. Priesthood office and Church position became a fluid alternative hierarchy, providing an effective mechanism for directing social and cultural change.

Other elements have combined with these to shape the distinctive aspects of LDS society. The Church did not, as did many rapidly growing Christian movements of the early nineteenth century, reject popular public entertainments. Indeed, excelling in fine arts, music, dance, drama, and other forms of cultural expression could be seen as a sacred obligation. Individual creative works were recognized and appreciated, but the more robust Mormon cultural expressions were those requiring unified action and cooperation. Moreover, the influx of immigrants—beginning in the 1840s from Great Britain and in the 1850s from Scandinavia—brought directly to Utah pioneer settlements institutions not as readily accessible to many other agrarian societies in the western United States.

Distinctive elements of social and cultural life in the first LDS areas—Kirtland, Ohio, and the various Missouri settlements—were related principally to religious activities. They included the designing and constructing of the Kirtland Temple (1836), with Aaronic and Melchizedek pulpits that corresponded to priesthood organization; the writing of hymns expressing distinctive beliefs; the forming of a choir to sing LDS hymns at the dedication of the Kirtland Temple; and the founding of the School of the Prophets to encourage both secular and religious learning. Popular amusements, vernacular architecture, and crafts were similar to those in other rural American districts, with the exception that horseracing and cardplaying were avoided. In the mid-1830s, the movement was as yet too young and the number of Latter-day Saints too few for either new doctrines or historical experience to have made them markedly different culturally from other Americans.

By the mid-1840s, however, some distinctive elements were becoming evident. Because earlier persecutions had reinforced a natural group solidarity, members looked inward and limited association with those not of their faith, whom they came to call gentiles. Resulting isolation focused the process of selecting and adapting cultural and social forms from the greater society, making them more distinctive. Nauvoo, illinois, a temporary respite from persecution, saw the largest group "gathered" yet, further favoring the development of distinctive social and cultural institutions. The division of Nauvoo into political "wards" led eventually to a practice of dividing Church membership into geographically defined congregations called wards. The ward was to become a social institution of first importance—perhaps the most powerful single instrument of LDS social organization.

Nauvoo also saw the introduction of temple-related teachings and practices that had important implications for social and cultural life. Baptism for the dead permitted Church members to be baptized as proxies for deceased ancestors; sealings united husbands and wives through eternity; and the Endowment, another ordinance with eternal implications, also strengthened group commitment to building together the kingdom of God. Celestial and plural marriage, popularly called polygamy, was taught privately (publicly in 1852); with the Law of Adoption, plural marriage extended the concept of family to incorporate all of society. (See Plural Marriage home page)

Some left the Church over Nauvoo innovations. Those who embraced the restoration of these additional doctrines and ordinances found themselves farther from a Protestant Christianity that came to seem increasingly hostile. The result was even stronger identity and solidarity among those who accepted the teachings and endured the opprobrium they engendered.

Folk amusements in Nauvoo were those commonly found elsewhere in the United States. The city had bowling alleys and billiard halls. Men engaged in horsemanship and in personal contests, such as foot races and wrestling matches. Swimming, an early version of baseball called "Old Cat," and fencing were popular recreations.

Intellectual life was encouraged by lyceums, a debating society, a lending library, and art exhibits. The Nauvoo charters provided for a university, which administered the public school system and kept salient the hope of developing an LDS-controlled intellectual center for the Saints—a hope not realized until the founding in Utah of the university of Deseret (1850), Brigham Young University (1875), and numerous academies. The times and seasons (1839-1846) continued a tradition of LDS journalism that had begun in 1832 with the publication of the evening and the morning star in Missouri (1832) and in Ohio (1832-1834), and would culminate in founding the Deseret news in 1850, which remains a Church-owned Salt Lake City daily newspaper.

Recent convert Gustavus Hills organized the Nauvoo Musical Lyceum in 1841. Partly through his efforts, choral music became so popular that in 1842 the women's Relief Society organized its own choir, as did several outlying settlements. These choirs continued throughout the Nauvoo period to sing a varied repertoire of religious, popular and even comedic songs, at both religious services and civic events. The first band to become an enduring institution was a twenty-piece ensemble, mostly percussion instruments and fifes. The band or other musicians provided music for the most popular entertainment in the city, dancing. Dances were held on every possible occasion and became an enduring feature of LDS social life. So important was music to the city's cultural life that in 1845 the Saints completed a Music Hall that would seat more than seven hundred persons.

In 1846 the Saints left Nauvoo for the West. That winter as many as 16,000 (by some estimates) gathered into settlements across Iowa and, especially, on both banks of the Missouri River (see Winter Quarters). Band and choral music, and dancing, continued even in these severe circumstances. Though advance parties reached Utah the next year, the settlements on the river's east bank, centered in Kanesville (see Council Bluffs), remained heavily LDS until 1852. This Iowa interlude (1846-1852) was of great importance in shaping LDS social and cultural institutions. Wards clearly became, for the first time, ecclesiastical jurisdictions with their own leaders and meeting schedules. Dancing, singing societies, and schools proliferated. The women, meeting frequently and informally, blessed and comforted one another and ministered to those needing assistance. Efforts were made to work the Law of Adoption and plural marriage into viable institutions that would enhance the cohesiveness of the larger community. Perhaps most important, the First Presidency was reorganized in December 1847, with Brigham Young, just returned from the Salt Lake Valley, being sustained in place of the martyred prophet. In Utah Brigham Young would take the lead in elaborating developments already begun in Nauvoo.

The earliest years of pioneering in Utah left little time for cultural and social activities beyond the perennial dancing, singing, and band music. But by 1852 the population was again sufficiently concentrated, this time in Salt Lake City, to recommence the ambitious agenda begun in Nauvoo. That winter Church leader Lorenzo Snow and his sister Eliza R. Snow organized the Polysophical Society, an informal discussion and debating society for men and women; comparable societies founded in many wards continued their activities throughout the decade. In 1853 a public lending library opened in the city. In 1852 Sicilian-born convert Domenico Ballo came to Salt Lake City with a band he had organized in St. Louis. The Ballo and the older William Pitt bands played, in addition to favorite hymns, such popular songs as "Auld Lang Syne," an occasional patriotic rendering of "Yankee Doodle" or "La Marseillaise," and selections from Mozart, Meyerbeer, and Rossini.

Choral music remained widespread and popular. In 1852 members revived the old Nauvoo choir. Because they performed first in the just-completed old adobe tabernacle and, after 1867, in a new tabernacle (which still graces Temple Square), it became known as the tabernacle choir. Eventually the "Mormon Tabernacle Choir" became one of the two or three most widely recognized symbols of the Latter-day Saints. Its several hundred members from different backgrounds express themselves as a unified, harmonious whole—the epitome of LDS cultural expression. In 1929 the choir began regular weekly network radio broadcasts, which continue.

Cultural life in early Salt Lake City was not limited to music. The Deseret Dramatic Association, organized in 1852, first performed in the old Social Hall. The Social Hall housed musical performances, balls, and receptions as well as theatrical productions. It was superseded in 1862 by the Salt Lake theatre, a lavish building seating 1,500 and constructed at some sacrifice, one of the important cultural institutions of the early west. The Deseret Dramatic Association maintained an ambitious repertory schedule, in some seasons performing three times a week. A typical program began with prayer, featured a long, serious play, and ended with a short comedy or farce.

Dancing was popular throughout the territory, and every community prized its fiddlers. Most holidays ended with a grand ball that might last until two or three in the morning. "Square dances," ordered in prescribed patterns like the Virginia Reel, were the usual fare. An occasional risqué round dance such as the waltz was permitted as the century wore on. In Salt Lake City the Social Hall routinely hosted dances; larger affairs could be held at the Salt Lake Theatre, whose orchestra seats could be covered by a spring floor.

Architecture in Salt Lake City was for the most part spare, practical, and derivative. Greek Revival style, ordered and simple, was as popular in Utah as elsewhere in the United States. The Gothic Revival style can be seen in the Salt Lake Temple, and in other buildings, notably, Brigham Young's residence, the Lion House. The Federal-style architecture of public buildings the Saints had used in the Midwest was replicated in the city hall and other early civic structures. Homes were generally simple adobe or brick, built in traditional or pattern-book styles and sometimes reflecting the ethnic background of the owner. Such homes were commonly symmetrical, ornamented according to the combined tastes of owner and builder, and designed to look complete while awaiting the addition of a second story or wing as family needs and means permitted.

The considerable variety seen in houses was contained by a rigid city plan, an adaptation of principles Joseph Smith recommended in his 1833 "plat of the city of Zion" (see City Planning). The plan called for homes of adobe, rock, or brick on large city lots uniformly set back from the broad, square-surveyed streets. A central square was set aside for the temple, and streets were named for their direction and distance from it. In outlying towns the central square contained churches, schools, and other civic structures. Farm land was outside the town proper. Early visitors were invariably impressed with the neatness and order of Mormon towns, always noting, in addition to the street pattern, the gardens, and the clear, mountain water that ran in small ditches along the streets.

This general pattern was followed in remote villages as well as in Salt Lake City. The compactness of the village system made it possible to sustain, even in towns with as few as two hundred or three hundred citizens, a full complement of bands and choirs, theater groups, and the ubiquitous community dances. Church leaders were acutely conscious of the social consequences of such a settlement pattern, pointing out in an 1882 letter the "many advantages of a social and civic character which might be lost…by spreading out so thinly that intercommunication is difficult, dangerous, inconvenient and expensive."

Despite the stress on group activities, there were several fine artists in early Utah. These included William W. Major, an accomplished painter, and C. C. A. Christensen, trained at the Royal Academy in Denmark, who painted faith-promoting scenes from LDS history. Norwegian convert Danquart A. Weggeland also did excellent work, mainly in painting sets for the Salt Lake Theatre and scenes in LDS temples and meetinghouses. George M. Ottinger worked extensively with historical representations, portraits, and landscapes.

Landscape painting played a lesser role in Utah art until, in the 1890s, John Hafen, Lorus Pratt, Edwin Evans, and John Fairbanks studied in Paris under Church sponsorship. They returned to devote their considerable talents to painting Church scenes adorning interiors of LDS temples. Alfred Lambourne and H. L. A. Culmer, also prominent landscape artists of this later period, emphasized the romantic qualities of Utah landscapes in a style worthy of the famous Rocky Mountain painters Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran. Since Latter-day Saints did not commonly use statuary in adorning church interiors, there was relatively little public demand for sculpture. Two early pieces are well known: the lion that dominated the entryway to Brigham Young's Lion House, and the eagle carved in 1859 by Ralph Ramsey for the entrance to Brigham Young's estate.

Early photographers Marsena Cannon, Charles W. Carter, Charles Savage, George Anderson, and Elfie Huntington did excellent work, often recording important events as well as everyday scenes in Utah folk life. The notable writers included Parley P. Pratt, Eliza R. Snow, Hannah Tapfield King, and Sarah Elizabeth Carmichael. Most of their work was devotional poetry, often set to music to become part of the rich repertoire of LDS hymnody. Newspapers and magazines were published wherever opportunity permitted, including manuscript newspapers laboriously copied by hand and circulated from house to house in smaller towns. For a time the Peep O'Day (1864) served the literary set in the capital. Thousands of diaries and journals kept by individuals, recording the routine of their lives and their interpretation of the world about them, provide an often eloquent literary legacy.

There have been several distinct periods in LDS social and cultural life, each influenced by a different relationship between the Saints and the society around them. From 1847 to 1857 the LDS community was relatively small and undisturbed. Ward organizations played a secondary role to the central community, and since almost all in Mormon communities were Church members, community endeavor was LDS endeavor. This began to change in 1857-1858 when the Utah expedition brought a large non-Mormon military and freighting population to Utah Territory. During the 1860s, the Civil War and gold and silver strikes in Utah and the surrounding territories brought a continuous stream of new settlers. That decade culminated in the completion of the transcontinental railroad, forever ending earlier autonomy and isolation.

As a more secular Utah sprang up, the Latter-day Saints, also growing in numbers, found themselves for the first time unable to dominate all the central public institutions. They responded by changing the center of community life from the Salt Lake downtown area to the dozens of individual wards. Each ward began to foster a full range of religious, educational, social, economic, recreational, and cultural activities designed to keep the growing numbers of young within the fold. Ward grammar schools, for example, avoided the secularization of public education, as did the later academies for secondary education.

Many wards founded cooperative stores as local outlets for the central Zion's Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI). In 1874 President Young took a dramatic step in founding the United Order of Enoch, a regionwide economic plan aimed at placing production and distribution under community-owned cooperatives. Though almost every ward organized an order, the plan had an important economic effect in only a few localities. Nonetheless the effort indelibly impressed upon Latter-day Saints the understanding that they would one day live and work under a celestial economic order based on cooperation and sharing.

Beginning in 1849, individual wards founded Sunday schools for children, their activities first coordinated on a Churchwide basis in 1872. The retrenchment association for young women was begun in 1869—its name changing in 1875 to the Young Women's Mutual Improvement Association (YWMIA), a complement to the Young Men's Mutual Improvement Association (YMMIA), also founded that year. Both societies aimed to provide a full complement of cultural and recreational activities for LDS youth, thus shielding them from the influences of the outside world. Even younger children were brought into this net of concern with the founding of the primary organization in 1878, which held weekly recreational and instructional programs for children between the ages of three and eight (later raised to eleven). Beginning in 1867, Relief Societies were reinstituted throughout the Church. They provided women an organization for mutual assistance that was concerned with maternal and child health matters, administering to the needs of the poor, socializing, and adult education. Their leaders also published the woman's exponent, which was discontinued in 1914 and replaced by the Relief Society magazine (1915-1970).

As these organizations proliferated, the Latter-day Saints were moving toward their ultimate confrontation with the federal government over plural marriage. By the end of the 1880s, the U.S. Congress had passed laws disincorporating the Church, taking over most of its properties, and disfranchising its women (see Antipolygamy Legislation). Faced with the destruction of the Church as an institution, in 1890 Church President Wilford Woodruff issued the manifesto and began the process of better integrating the Saints into American society. Whereas in the 1860s Latter-day Saints had responded to the broader society by creating complete ward-centered societies, they now involved themselves in secular workplaces and civil governance, and sent their children to public schools. Ward schools fell into disuse, between 1913 and 1924 many Church-sponsored academies were closed, and ward stores were sold to private entrepreneurs.

Still, the Church remained committed to institutional responses that helped meet the needs of members in a changing world. Though they could not duplicate tax-supported public schools, they began in 1912 to build seminary buildings near high schools, where Church-supported religious instruction (and social and recreational activities) could be offered to LDS youth. In the 1920s, they extended the same concept to higher education with the institute program (see Church Educational System). Leaders stressed as never before the importance of attending Church services regularly. They gave new emphasis to observance of the Word of Wisdom, a health code revealed in 1833, as a principal index of faithfulness and group identity. Determined to co-opt entertainments popular in the outside world, they sponsored parallel activities—they were always opened with prayer, were alcohol and tobacco free, and were carefully chaperoned. If in the secular world competition in sports became popular, the Latter-day Saints would found their own leagues. If public dances were tempting youth, they would have more and better dances.

Through Mutual Improvement Associations (MIA), Relief Societies, Primary, and the various priesthood quorums, ward bishops administered a remarkable array of social and cultural activities, involving youth and adults in choirs, dancing, speech, drama, and sports. In 1895 the MIAs founded the "Mutual Improvement League," opening gymnasiums that sponsored athletic and fitness programs for men and women. After this league's demise, the YMMIA and the University of Utah built Deseret Gymnasium in 1910 to foster physical fitness in a wholesome environment.

As team sports became more popular in the broader society, the Church began to sponsor these activities within the wards as well. Beginning in 1901, Church leaders held a special "June conference" annually for the Mutual Improvement Associations. Leaders sponsored an athletic field day in connection with the 1904 conference, an event that continued for some years. By 1906 baseball, basketball, and track and field competitions were being held among the various wards, and in 1910 the General Board of the MIA set up a standing "Committee on Athletics and Field Sports."

One consequence of this Church sponsorship of athletics was the development of Churchwide tournaments and competitions. Young men of 17-24 years ("M-Men") held their first Churchwide basketball tournament in 1922 and added a softball tournament in 1934. Boys were at first not deemed physically capable of the strenuous sport of basketball, so a new sport, "Vanball," was invented, combining elements of basketball and volleyball; it was played in competition until the end of World War II. From World War II until the 1960s the Church held competitions at both senior and junior levels in basketball, softball, volleyball, and golf, with more than a thousand teams from the United States, Canada, and Mexico competing for the chance to play in all-Church tournaments. Tennis tournaments also were held in the 1950s, but were dropped partly because, as an individual sport, tennis was not the kind of "mass participation" activity the Church had generally favored.

Beginning with the exercise and fitness movement at the turn of the century, sports activities for young women somewhat paralleled those for young men but lagged behind a little. Young women participated fully in annual sports field days. Later came camping programs that, by 1950, saw as many as 20,000 girls certifying annually. Because wards and stakes had flexibility to meet local needs and interests, compared with young men's athletics, the girls' team program varied widely. A swimming achievement program and all-Church golf and tennis tournaments accommodated individual young women who wished to participate. Eventually young women competed in volleyball, softball, and basketball, and by the 1970s sports opportunities for young men and women were generally comparable.

In addition to social dances in ward meetinghouses, dance festivals with colorful pageantry became a common feature of June Conference. Beginning in the 1930s, "Road Show" competitions were held at stake and higher levels, the youth of each ward (with leaders) preparing an original fifteen-minute musical that could quickly be moved from meetinghouse to meetinghouse, so that members of each congregation could enjoy an evening of theatricals in their own neighborhood. Youth also competed for local, stake, and general awards in speech.

The primary site for all of these activities was the local ward meetinghouse. In one sense the home became a place from which the Saints commuted to their main center of socializing and worship—the ward meetinghouse. Ward activities occupied at least some family members part of virtually every day of the week, much of Saturday, and most of Sunday. Because Latter-day Saints learned to see the meetinghouse as the primary place for socializing, it was difficult for those not part of the ward to become part of their world.

Though the ward still remains the center of social and cultural life for committed Latter-day Saints, since the 1960s Church leaders have initiated changes that have diminished its role as the focal point of LDS neighborhoods and communities. A consolidated meeting schedule greatly reduced the amount of time spent at the meetinghouse. A more restricted definition of Church purposes, "to spread the gospel, perfect the Saints, and redeem the dead," called into question the relevance of Church-sponsored cultural and social activities not contributing to these aims. Reallocating tithing funds to pay ward expenses reduced the need to cooperate in fundraising events to pay for socials and other activities. With both construction and maintenance of buildings managed by centrally funded contract, meetinghouses were no longer a product of community labor and sacrifice. At the same time, Churchwide competitions in speech, drama, and athletics were discontinued, leaving strong regional competition in some areas and perhaps less incentive for good local programs in others.

Church leaders saw gains in these new initiatives that would outweigh the losses. The great sacrifices members had made to sustain the many ward and Church programs would be reduced. There would also be a better distribution of Church resources, with more equality across geographical and class lines. Though the Saints in heavily LDS Utah might have a leaner program, members in developing areas could have more.

Latter-day Saints have proudly borne the stamp of being "a peculiar people," an identity that helped maintain the energy and commitment that characterized the classic, close-knit ward community. Some observers feel that this cohesive sense of community is the genius of LDS society. Latter-day Saints face the challenge of maintaining that cohesiveness and their sense of special identity and mission in a complex, changing world. Bereft of many occasions when the Saints traditionally were brought together to worship, work, and play, LDS society must continue to adjust or it could lose its focus. Drawn out of the broader society by faith in the Restoration, early Latter-day Saints learned to select and adapt cultural and social forms upon which they put a distinctive and compelling stamp. As the Church expands internationally, that process must continue. The challenge facing the Church in the twenty-first century is to find ways to maintain that energy and develop that sense of identity among peoples of diverse cultures throughout the world.

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page)

Illustrations

Saltair (c. 1920). This resort on the Great Salt Lake, west of Salt Lake City, was built by the Church in 1893 as a contribution to the greater community in the area. it burned in 1925 and was rebuilt a number of times thereafter, but is no longer standing. Photographer: Albert Wilkes. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Actress Maude Adams was born in Salt Lake Valley in 1872. Her mother was a regular performer in the Social Hall and Salt Lake Theatre, for which her father furnished timber. Her career on stage in new york earned her a reputation for charm and naturalness. Young Woman's Journal 14 (June 1903):244-249. Photographer: Charles Ellis Johnson. Courtesy Rare Books and Manuscripts, Brigham Young University.

Bibliography

No comprehensive study exists of the social and cultural history of the Latter-day Saints. Much useful material can be gleaned from studies of particular periods of LDS history; see bibliographies accompanying History of the Church entries. See also bibliographies for articles on Education, Music, Dance, Sports, Art, Artists, Sculpture, and Drama. Also helpful is Davis Bitton, "Early Mormon Lifestyles; or the Saints as Human Beings," in The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History, ed. F. Mark McKiernan et al. Lawrence, Kans., 1973.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 3, Social and Cultural History

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |