Utah Expedition |

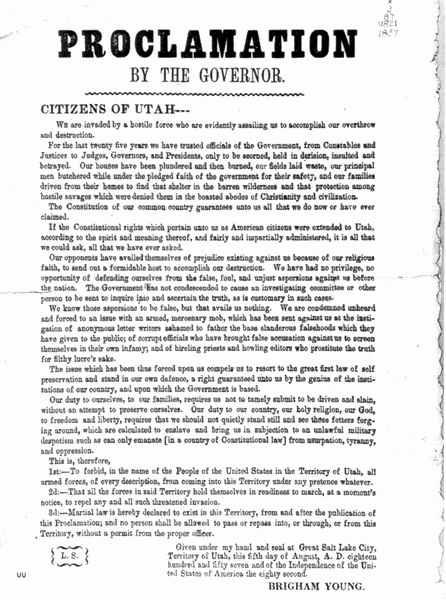

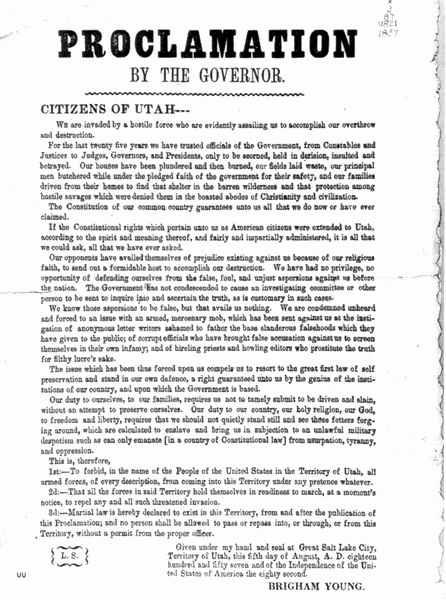

In Defense against the approach of Johnston's army, Brigham Young posted this proclamation throughout Utah Territory on August 5, 1857, declaring martial law and forbidding any person to pass in or through the territory without permission from an authorized officer. Courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Utah Libraries.

by Richard D. Poll

The Utah War of 1857-1858 was the largest military operation in the United States between the times of the Mexican War and the Civil War. It pitted the Mormon militia, called the Nauvoo Legion, against the army and government of the United States in a bloodless but costly confrontation that stemmed from the badly handled attempt by the administration of President James Buchanan to replace Brigham Young as governor of Utah Territory. It delayed, but did not prevent, the installation of Governor Alfred Cumming, and it had a significant impact on the territory, its predominantly Latter-day Saint inhabitants, and the Church itself. Because the conflict resulted from misunderstandings that were distorted by time and distance, had the transcontinental telegraph been completed in 1857 instead of 1861, the expedition almost certainly would not have occurred.

The decision to replace Governor Young was inevitable, given the national reaction to the Church's 1852 announcement of plural marriage and Republican charges in the campaign of 1856 that the Democrats favored the "twin relics of barbarism"—polygamy and slavery. The method chosen to implement that decision, however, is still puzzling. Apparently influenced by reports from Judge W. E. Drummond and other former territorial officials, Buchanan and his cabinet decided that the Latter-day Saints would reject a non-Mormon governor. So, without investigation, mail service to Utah was suspended and 2,500 troops led by Albert Sidney Johnston were ordered to accompany Cumming to Great Salt Lake City.

Remembering earlier difficulties with troops and perhaps swayed by the ardor of the recent reformation movement (see Reformation [LDS] of 1856-1857), Church leaders interpreted the army's unannounced coming as religious persecution and decided to resist. Brigham Young, still acting as governor, declared martial law and deployed the Nauvoo Legion to delay the troops with "scorched earth" tactics. Harassing actions, including burning three supply trains and capturing hundreds of government cattle, forced Johnston's expedition and the accompanying civil officials into winter quarters at Camp Scott and Eckelsville, near burned-out Fort Bridger, some 100 mountainous miles east of Salt Lake City.

During the winter both sides strengthened their forces. Congress, over almost unanimous Republican opposition, authorized two new volunteer regiments, and Buchanan, Secretary of War John B. Floyd, and Army Chief of Staff Winfield Scott assigned 3,000 additional regular troops to reinforce the Utah Expedition. Meanwhile, Utah communities were called upon to equip a thousand men for a spring campaign. Predictions of hostilities came from LDS pulpits, Camp Scott, and the national press.

There is persuasive evidence, however, that Brigham Young never intended to force a military showdown. He and other leaders often spoke of abandoning and burning their settlements rather than permitting their occupation by enemies, as had happened in Missouri and Illinois.

That Brigham Young hoped for a diplomatic solution is clear from his early appeal to Thomas L. Kane, the influential Pennsylvanian who had for ten years been a friend of the Mormons. Soon after Christmas, Kane received Buchanan's permission to go to Utah, via Panama and California, as an unofficial mediator. Reaching Salt Lake City late in February, he found Church leaders ready for peace but distrustful. When the first reports of Kane's contacts with General Johnston were discouraging, the apprehension was reinforced.

The "Move South" resulted. President Young announced on March 23, 1858, that all settlements in northern Utah must be abandoned and prepared for burning if the army came in. The evacuation started immediately. Though at first perceived as likely to be permanent, the Move South was transformed into a tactical and temporary maneuver soon after word came that Kane had persuaded Cumming to come to Salt Lake City without the army. Still, in numbers at least, it dwarfed the earlier Mormon flights from Missouri and Illinois: about 30,000 people moved fifty miles or more to Provo and other towns in central and southern Utah. There they remained in shared and improvised housing until the Utah War was over.

When Kane and Cumming arrived early in April, Young surrendered his political title and soon formed an amiable working relationship with his successor. However, the Move South continued, probably because the government representatives insisted that Johnston's troops must be admitted but were unable to guarantee that they would come in peacefully.

Meanwhile, President Buchanan responded to rising criticism by appointing Lazarus Powell and Ben McCulloch to carry an amnesty proclamation to Utah. Arriving early in June, they found Church leaders willing to accept Cumming and a permanent army garrison in exchange for peace and amnesty. Johnston's army marched through a largely deserted Salt Lake City on June 26, 1858, and went on to build Camp Floyd forty miles to the southwest. Soon the refugees returned home; the Utah War was over.

From this episode the Buchanan administration reaped an unbalanced defense budget and some political embarrassment. With a fair and impartial approach, Governor Cumming soon became more popular with the Latter-day Saints than with the military. Camp Floyd and the nearby civilian town of Fairfield represented the first sizable non-Mormon resident population in Utah. Though the troops left Utah at the outbreak of the Civil War, the presence for three years of thousands of troops and camp followers ended the Latter-day Saint dream of a Zion geographically separate and distant from the world of unbelievers.

As for the LDS community in Utah, the exertions and expenditures strained both capital and morale. Defense efforts terminated some of the Mormon outpost settlements in present-day California, Nevada, Wyoming, and Idaho, interrupted and weakened the missionary effort in Europe, curtailed immigration, and dissipated much of the enthusiasm and discipline generated by the Reformation of 1856. Unsympathetic, if not hostile, troops and camp followers influenced economics, politics, and lifestyles. The Move South won media sympathy, but it also disrupted Latter-day Saint community and religious life and did little to increase the toleration for Mormon differences from mainstream American ideas and institutions.

In spite of the posturing and bumbling of those involved, what seemed like an inevitable military confrontation was ultimately resolved peacefully. The tensions, differences, and misunderstandings that preceded the resolution, however, remained, and it would be nearly forty years before Utah would be accepted as a state (see Utah Statehood).

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page; 1844-1877 home page)

Bibliography

Furniss, Norman F. The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859. Westport, Conn., 1977.

Poll, Richard D. Quixotic Mediator: Thomas L. Kane and the Utah War. Ogden, Utah, 1985.

Poll, Richard D. "The Move South." BYU Studies 29 (Fall 1989):65-88.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 4, Utah Expedition

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |