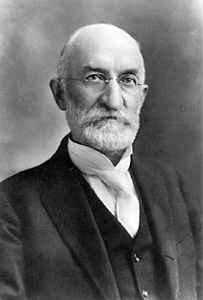

Heber J. Grant |

On November 23, 1918, Heber J. Grant was sustained as the seventh President of the Church. His twenty-six year administration was noted for placing the Church on a sound financial basis, expanding the role of education in the Church, and establishing the modern Church welfare program. Photographer; Charles R. Savage.

by Ronald W. Walker

Heber J. Grant (1856-1945), seventh President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was a business leader and a devoted follower of the gospel of Jesus Christ who used his talents in the service of his Church. As an apostle, he was instrumental in preserving Mormonism's credit and reputation after the economic devastation of the Panic of 1893. As President, he was a model of strong character and an ambassador of goodwill to a world often hostile to the Latter-day Saints.

Born November 22, 1856, in Salt Lake City to Jedediah M. and Rachel Ridgeway Ivins Grant. Heber associated from a young age with Church and territorial leaders. His father served as Brigham Young's counselor in the First Presidency and as mayor of the city, and his mother enjoyed the society of the leading women of the LDS community.

Heber did not benefit from the association of his father directly. Jedediah Grant died nine days after Heber was born, the victim of "lung disease," and Rachel became the paramount influence in Heber's life. Prim and reserved, she came from a New Jersey family of merchants and devoted practitioners of religion. She joined the Church just prior to her twentieth birthday, in part because of the labors of the fiery missionary who later became her husband. In 1855, Rachel became one of Jedediah's plural wives.

After Jedediah's death, diminished means eventually forced Rachel and her son to move from the substantial Grant home on Main Street to a "widow's cabin" several blocks away. The change was wrenching. Declining the proffer of Church aid, Rachel supported the family by sewing and taking in boarders. Young Heber sat on the floor many an evening and pumped the sewing machine treadle to relieve his weary mother.

The location of the Grants' new home placed them within the Salt Lake Thirteenth Ward, one of the largest and most culturally diverse LDS congregations in the territory, and so Heber enjoyed the best of frontier Mormonism. He was one of the few youths of the city to serve as a "block teacher," and at the unusually young age of fifteen he was ordained to the office of seventy in the priesthood.

In the absence of public schools, Rachel found the means to enroll her son in good private schools, beginning with Brigham Young's school at State and South Temple streets. Grant remembered himself as being good at mathematics, memorization, and recitation, but less gifted in grammar, spelling, and especially foreign languages. Following frontier practice, his class experience was limited; he left school at the age of sixteen.

When the Thirteenth Ward organized the first Young Men's Mutual Improvement Association (YMMIA) in 1875, Grant was called as a counselor to its president at age nineteen. The YMMIA's weekly sessions gave him a chance for study, self-improvement, and speech-making. On his own he read LDS and Protestant devotional literature, Samuel Smiles' chatbooks idealizing the self-made man, and books of readings filled with firm and traditional values. As a young man, he was an active member of the "Wasatch Literary Association," a high-spirited local group that met each Wednesday evening for cultural exercises. These might include declamations, lectures, debates, readings, musical renditions, and even small-scale theatrical productions. In later years he often acknowledged his debt to the "Wasatchers" for much of his cultural and intellectual training.

For several years business became Grant's preoccupation. In addition to selling insurance, he peddled books, found Utah retailers for a Chicago grocery house, performed tasks for the Deseret National Bank, and taught penmanship. With Brigham Young's support, he was appointed assistant cashier of the Church-owned Zion's Savings and Trust Company. Hard work began to pay dividends. A typical Utah wage earner might make $500 annually; in his early twenties, Grant earned ten times that amount. Soon he opened another insurance agency in Ogden and began to fulfill his hope of developing "home industry." With a partner, he purchased the Ogden Vinegar Works.

On October 30, 1880, Grant was called as president of the Tooele Stake, about twenty-five miles west of Salt Lake City. Not yet twenty-four years old, he presided over more than a half-dozen congregations, dispensing spiritual and temporal counsel to frontier-hardened and not always pliant settlers. Moreover, the area presented one special difficulty: with the opening of western Utah mines, non-Mormons had settled in the county and for a time wrested local political control from the Church.

To Grant's new challenges were added personal difficulties. He had married a longtime acquaintance from the Thirteenth Ward, Lucy Stringham, on November 1, 1877, three weeks before his twenty-first birthday. Shortly after the couple moved to Tooele, she developed a lingering stomach illness and related problems that twelve years later claimed her life. Not long after, his Salt Lake City businesses began to suffer from lack of attention. His Ogden vinegar factory burned, and he was underinsured.

Although he enjoyed ministering to his Tooele flock, his personal difficulties weighed heavily on him. He later admitted that during these years he felt so "blue" that he did not know what to "do or where to turn" (Grant to B. F. Grant, July 21, 1896, Grant Papers, LDS Archives). Under this burden, his six-foot, 140-pound frame almost gave way. The attending doctor pronounced a diagnosis of "nervous convulsions" and warned the young man that if he did not slow his pace he would certainly experience a "softening of the brain" (Grant typed diary, Nov. 1, 1887; Francis M. Lyman diary, Jan. 7, 15, 16, 23, 1882, Church Archives).

In 1882, less than two years after his arrival in Tooele and ten months after his nervous collapse, Grant was asked to attend a council meeting in Church President John Taylor's office, where President Taylor announced a revelation filling two vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. As the document was read, Grant learned of his appointment to the quorum. He felt unprepared to serve in what he believed was such a high and important calling. He also wondered whether his relish for commerce properly mixed with religion. Grant's troubled "long night of the soul" was resolved during one of his first preaching tours. While traveling in Arizona, he had a spiritual manifestation that confirmed his call and put an end to his self-doubts. The epiphany also affirmed several blessings that Grant had received while a youth. On several occasions, Church leaders had prophesied his eventual high Church service.

During Grant's early service as an apostle, he concluded that wealth and money-making were honorable when dedicated to the common good, by which he meant two things: almsgiving and the founding of businesses to aid the Church and community. During his years as a young apostle, he did both. His gifts to friends and worthy purposes often took a third of his income. At a time when apostles commonly engaged in private activities, he was tireless in founding and developing "home institutions" to benefit the community. The enterprises included a Utah retail and wholesale business, a livery stable, two "home" insurance companies, a bank, a Salt Lake newspaper, the famed Salt Lake Theatre, the Utah Sugar Company, and a series of less prominent enterprises.

He was equally busy with Church assignments as a member of the Church Salary Committee, the Sunday School Board, and the Mutual Improvement superintendency. Twice he proselytized among the dangerous Yaqui Indians in Mexico, and his many tours to the Southwest earned him the title "the Arizona Apostle."

Grant eventually married three wives, who bore him twelve children. In addition to Lucy Stringham, he entered into plural marriage with Huldah Augusta Winters and Emily Wells. The three Grant wives were similar in many ways. Well educated for the times, all had taught school, and each descended from old pioneer families. "One's wealth consists in those whom he loves and serves and who love and serve him in return," he often said. Incessant travel took him away from the family, an absence he bridged by his long and sensitive personal letters. More than 50,000 letters are preserved in the Church archives, many of them to his children and grandchildren.

The Panic of 1893 caught both Grant and the Church overextended and eventually caused him to go to New York City to negotiate credit for himself and the Church. His loan brokering allowed him and the Church to remain solvent during the hard times of the 1890s, but the effects of the panic were severe for him personally; he lost his fortune and never fully recovered it.

As Utah and the Church entered the twentieth century, Grant's ministry changed. The growing Church required more and more of his time. He filled two foreign assignments, opening the Japanese Mission (1901-1903) and later presiding over the European Mission (1903-1905). On returning to the United States, he was assigned to supervise Church education, the Genealogical Society, and the Church magazine, the Improvement Era. He also still found time for community service, including assisting the cause of prohibition and directing World War I Liberty Bond drives.

In 1916 his seniority brought him to the presidency of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. Two years later, Church President Joseph F. Smith, on his deathbed, took Grant's hand and said, "The Lord bless you, my boy, the Lord bless you. You have got a great responsibility. Always remember that this is the Lord's work and not man's. The Lord is greater than any man. He knows whom he wants to lead his Church and never makes any mistake. The Lord bless you" (CR, Apr. 1941). On November 23, 1918, Heber J. Grant was sustained as President of the Church.

During his twenty-six-and-a-half-year administration—the Church's second longest—Church members grew familiar with the hardy, pioneer themes of President Grant's leadership. He repeatedly spoke of the need for charity, duty, honor, service, and work, and admonished the Saints to live modestly and to observe the prohibitions of the Church's health code, the Word of Wisdom. For Saints disoriented by the century's rapid social and cultural changes, President Grant's firm voice, ramrod-straight posture, and forceful—and sometimes sharp-tongued—delivery conveyed strength and resolution. He personified time-tested values.

After years of adverse Church publicity and misunderstanding, President Grant gladly accepted invitations to speak to non-Mormon groups throughout the United States, often traveling with his sole surviving wife, Augusta, in the hope of improving the image of the Church. He usually mixed personal reminiscence, business homilies, and a message about the Church. His influence was not limited to formal addresses. He cultivated personal contacts with business, cinema, media, and political leaders in the hope of presenting the Church in a more sympathetic light to the public at large. The production of such pro-LDS Hollywood films as Union Pacific and Brigham Young was partly due to his quiet influence. He promoted national tours by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and supported the political activity of Utah senator and LDS apostle Reed Smoot, whose growing national influence brought favorable comment to Utah and the Church.

Faced with regional and then national economic depression during the late 1920s and the 1930s, the Grant administration had to cope with hard times. In keeping with the lessons learned during the depressed 1890s, President Grant trimmed Church expenses wherever he could; also his business experience, and particularly his eastern contacts, repeatedly helped to stabilize the Church financially. He advised a number of local businesses—both Mormon and non-Mormon concerns—without compensation, helping to pull them through the difficult times. Moreover, in 1936 the Church under his leadership sought to assist impoverished Latter-day Saints by establishing the Church Security Program, later renamed the Church Welfare Program, one of the major accomplishments of his administration (see Welfare; Welfare Services). To help get it established, President Grant gave the program his large dry farm in western Utah, in which he had invested more than $80,000.

During his time as president, he dedicated three new temples: Laie, Hawaii (1919), Cardston, Canada (1923), and Mesa, Arizona (1927). Several hundred chapels were constructed, many in areas outside the Utah heartland. The Washington, D.C., chapel, dedicated in 1933, symbolized Church growth nationally.

Many of the characteristics of the Church in the twentieth century came into focus during President Grant's administration. Religious education received new emphasis with the establishment of an extensive seminary and institute program to provide a spiritual dimension in the education of the youth. Under his direction, Church leaders stressed Sacrament meeting attendance, temple activity, observance of the Word of Wisdom, family-history research, and monthly visits to Church members in their homes. To cope with the expansion of the Church, he called a new group of General Authorities, Assistants to the Twelve Apostles.

Near the end of his life and under his direction, the First Presidency addressed the moral perplexities of war. A statement issued at the beginning of World War II said, "The Church…cannot regard war as a righteous means of settling international disputes." Yet the statement urged allegiance to "constitutional law" and acceptance of national military service, whatever the nationality of Church members (IE 45 [May 1942]:348-49). The scrupulously neutral statement reflected President Grant's own reservations about American entrance into the conflict and his growing personal pacifism.

Members came to love President Grant's expansive ways. Until mounting burdens and declining health intervened, his office door was open to General Authorities, stake and local leaders, and even to members troubled with problems. He traveled widely throughout America and in 1937 heralded the Church's European centennial by touring the missions of Great Britain and western Europe, the second LDS President to venture across the Atlantic Ocean while in office. Seeking to personalize his presidency, he distributed thousands of homiletic books, personally autographing each and sometimes marking passages for emphasis. Recalling his mother's struggles, he freely gave of his personal means, particularly to widows, and established a missionary fund for his increasing progeny.

In 1940, while visiting Southern California, he suffered a series of strokes that slowed his pace and forced him to delegate active administration of the Church, relying primarily on J. Reuben Clark, Jr., his first counselor. President Grant died on May 14, 1945, at Salt Lake City.

During President Grant's administration Church membership doubled. He traveled more than 400,000 miles, filled 1,500 appointments, gave 1,250 sermons, and made 28 major addresses to state, national, civic, and professional groups. His greatest achievements, however, cannot be measured statistically. During almost sixty-five years of Church service, he helped transform the Church from a sequestered, misunderstood, pioneer faith to an accepted, vibrant religion of twentieth-century America.

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page; People in Church History home page)

Bibliography

No modern, full-scale biography of Heber J. Grant exists. For admiring surveys, see Bryant S. Hinckley, Heber J. Grant: Highlights in the Life of a Great Leader (Salt Lake City, 1951); Francis M. Gibbons, Heber J. Grant: Man of Steel, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City, 1979); and Ronald W. Walker, "Heber J. Grant," in The Presidents of the Church, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City, 1986).

For accounts of various events of Grant's life, see Ronald W. Walker, "Crisis in Zion: Heber J. Grant and the Panic of 1893," Arizona and the West 21 (Autumn 1979):257-78, reprinted in Sunstone 5 (Jan.-Feb. 1980):26-34; "Heber J. Grant and the Utah Loan and Trust Company," Journal of Mormon History 8 (1981):21-36; "Young Heber J. Grant: Entrepreneur Extraordinary," The Twentieth Century American West, Charles Redd Monographs in Western History, (1983):85-119; and "Young Heber J. Grant's Years of Passage," BYU Studies 24 (Spring 1984):131-49.

For his role in stabilizing Church finances in the early twentieth century, see Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana, Ill., 1986).

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 2, Grant, Heber J.

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |