by William O. Nelson Anti-Mormonism includes any hostile or polemic opposition to Mormonism or to the Latter-day Saints, such as maligning the founding prophet, his successors, or the doctrines or practices of the Church. Though sometimes well intended, anti-Mormon publications have often taken the form of invective, falsehood, demeaning caricature, prejudice, and legal harassment, leading to both verbal and physical assault. From its beginnings, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its members have been targets of anti-Mormon publications. Apart from collecting them for historical purposes and in response to divine direction, the Church has largely ignored these materials, for they strike most members as irresponsible misrepresentations. Few other religious groups in the United States have been subjected to such sustained, vitriolic criticism and hostility. From the organization of the Church in 1830 to 1989, at least 1,931 anti-Mormon books, novels, pamphlets, tracts, and flyers have been published in English. Numerous other newsletters, articles, and letters have been circulated. Since 1960 these publications have increased dramatically. A major reason for hostility against the Church has been its belief in extrabiblical revelation. The theological foundation of the Church rests on the claim by the Prophet Joseph Smith that God the Father, Jesus Christ, and angels appeared to him and instructed him to restore a dispensation of the gospel. Initial skepticism toward Joseph Smith's testimony was understandable because others had made similar claims to receiving revelation from God. Moreover, Joseph Smith had brought forth the Book of Mormon, giving tangible evidence of his claim to revelation, and this invited testing. His testimony that the book originated from an ancient record engraved on metal plates that he translated by the gift and power of God was considered preposterous by disbelievers. Hostile anti-Mormon writing and other abuses grew largely out of the perceived need to supply an alternative explanation for the origin of the Book of Mormon. The early critics focused initially on discrediting the Smith family, particularly Joseph Smith, Jr., and attempted to show that the Book of Mormon was entirely of nineteenth-century origin. Later critics have focused more on points of doctrine, individual leaders, and Church operation.

One of many political cartoons from the late nineteenth century, depicting Mormonism as a despotic, ignorant, adulterous threat to society. Charles W. Carter Collection.

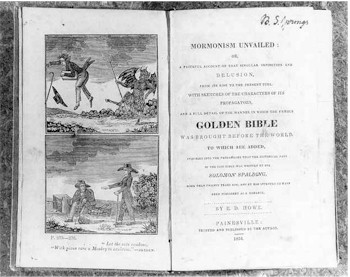

EARLY CRITICISMS (1829-1846). Joseph Smith's disclosure that heavenly messengers had visited him was met with derision, particularly by some local clergymen. When efforts to dissuade him failed, he became the object of ridicule. From the time of the first vision (1820) to the first visit by the angel Moroni (1823), Joseph "suffered every kind of opposition and persecution from the different orders of religionists" (Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith, p. 74). The first serious attempt to discredit Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon was by Abner Cole, editor of the Reflector, a local paper in Palmyra, New York. Writing under the pseudonym Obadiah Dogberry, Cole published in his paper extracts from two pirated chapters of the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, but was compelled to desist because he was violating copyright law. Cole resorted to satire. He attempted to malign Joseph Smith by associating him with money digging, and he claimed that Joseph was influenced by a magician named Walters. Alexander Campbell, founder of the Disciples of Christ, wrote the first published anti-Mormon pamphlet. The text appeared first as articles in his own paper, the Millennial Harbinger (1831), and then in a pamphlet entitled Delusions (1832). Campbell concluded, "I cannot doubt for a single moment that [Joseph Smith] is the sole author and proprietor of [the Book of Mormon]." Two years later he recanted this conclusion and accepted a new theory for the origin of the Book of Mormon, namely that Joseph Smith had somehow collaborated with Sidney Rigdon to produce the Book of Mormon from the Spaulding Manuscript (see below). The most notable anti-Mormon work of this period, Mormonism Unvailed (sic), was published by Eber D. Howe in 1834. Howe collaborated with apostate Philastus Hurlbut, twice excommunicated from the Church for immorality. Hurlbut was hired by an anti-Mormon committee to find those who would attest to Smith's dishonesty. He "collected" affidavits from seventy-two contemporaries who professed to know Joseph Smith and were willing to speak against him. Mormonism Unvailed attempted to discredit Joseph Smith and his family by assembling these affidavits and nine letters written by Ezra Booth, also an apostate from the Church. These documents allege that the Smiths were money diggers and irresponsible people. Howe advanced the theory that Sidney Rigdon obtained a manuscript written by Solomon Spaulding, rewrote it into the Book of Mormon, and then convinced Joseph Smith to tell the public that he had translated the book from plates received from an angel. This theory served as an alternative to Joseph Smith's account until the Spaulding Manuscript was discovered in 1884 and was found to be unrelated to the Book of Mormon. The Hurlbut-Howe collection and Campbell's Delusions were the major sources for nearly all other nineteenth- and some twentieth-century anti-Mormon writings, notably the works of Henry Caswall, John C. Bennett, Pomeroy Tucker, Thomas Gregg, William Linn, and George Arbaugh. Most of these writers drew routinely from the same body of anti-Mormon lore (see H. Nibley, "How to Write an Anti-Mormon Book," Brigham Young University Extension Publications, Feb. 17, 1962, p. 30). Perhaps the most infamous manifestation of anti-Mormonism came in the Missouri conflict, during which Governor Lilburn W. Boggs issued an Extermination Order. "The Mormons," he wrote, "must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state, if necessary for the public good" (HC 3:175). This order led to the expulsion of the Mormons from Missouri and their resettlement in Illinois. While incarcerated in Liberty Jail in 1839, Joseph Smith wrote to the Saints and instructed them not to respond polemically but to "gather up the libelous publications that are afloat; and all that are in the magazines, and in the encyclopedias, and all the libelous histories that are published, and are writing, and by whom" so that they could bring to light all misleading and untruthful reports about the Church (D&C 123:4-5, 12-13). This procedure has been followed by Latter-day Saints over the years. After the Saints moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, a principal antagonist was Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal. Alarmed over the Church's secular power, he used his paper to oppose it. In 1841 he published Mormonism Portrayed, by William Harris. Six notable anti-Mormon books were published in 1842. The first was The History of the Saints; or, An Exposé of Joe Smith and Mormonism, by John C. Bennett, who had served as Joseph Smith's counselor in the First Presidency and was also the first mayor of Nauvoo. After he was excommunicated from the Church for immorality, he turned against the Mormons and published a series of letters in a Springfield, Missouri, newspaper. He charged that Joseph Smith was "one of the grossest and most infamous impostors that ever appeared upon the face of the earth." Bennett's history borrowed heavily from Mormonism Portrayed. That same year, Joshua V. Himes published Mormon Delusions and Monstrosities, which incorporated much of Alexander Campbell's Delusions. The Reverend John A. Clark published Gleanings by the Way, and Jonathan B. Turner, Mormonism in All Ages. Both books relied heavily on Howe and Hurlbut's Mormonism Unvailed. Daniel P. Kidder's Mormonism and the Mormons expanded the Spaulding theory of Book of Mormon origins to include Oliver Cowdery in addition to Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon. Called the "Anti-Mormon Extraordinaire," the Reverend Henry Caswall published The City of the Mormons, or Three Days at Nauvoo. He claimed that he gave Joseph Smith a copy of a Greek manuscript of the Psalms and that Smith identified it as a dictionary of Egyptian hieroglyphics. Caswall invented dialogue between himself and Smith to portray Joseph Smith as ignorant, uncouth, and deceptive. In 1843 Caswall published The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century in London, borrowing most of his material from Clark and Turner. By 1844 Joseph Smith also faced serious dissension within the Church. Several of his closest associates disagreed with him over the plural marriage revelation and other doctrines. Among the principal dissenters were William and Wilson Law, Austin Cowles, Charles Foster, Francis and Chauncey Higbee, Charles Ivins, and Robert Foster. They became allied with local anti-Mormon elements and published one issue of a newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. In it they charged that Joseph Smith was a fallen prophet, guilty of whoredoms, and dishonest in financial matters. The Nauvoo City Council and Mayor Joseph Smith declared the newspaper an illegal "nuisance" and directed the town marshal to destroy the press. This destruction inflamed the hostile anti-Mormons around Nauvoo. On June 12, 1844, Thomas Sharp's newspaper, the Warsaw Signal, called for the extermination of the Latter-day Saints: "War and extermination is inevitable! Citizens arise, one and all!!! Can you stand by, and suffer such infernal devils! to rob men of their property and rights, without avenging them…. Let [your comment] be made with powder and ball!!!" Two weeks later Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were assassinated in Carthage Jail while awaiting trial on charges of treason. Sharp defended the killing on the grounds that "the most respectable citizens" had called for it. Sharp and four others eventually were tried for the murders, but were acquitted for lack of evidence. Many felt that the Church would die with its founders. When the members united under the leadership of the Twelve Apostles, anti-Mormon attacks began with new vigor. Sharp renewed his call for the removal of the Mormons from Illinois. By September 1845, more than 200 Church members' homes were burned in the outlying areas of Nauvoo. In February 1846, the Saints crossed the Mississippi and began the exodus to the West. Revenge was possibly a motive of some anti-Mormons, especially apostates. Philastus Hurlbut, Simonds Ryder, Ezra Booth, and John C. Bennett sought revenge because the Church had disciplined them. Alexander Campbell was angered because he lost many of his Campbellite followers when they joined the Latter-day Saints. Mark Aldrich had invested in a real-estate development that failed because Mormon immigrants did not support it, and Thomas Sharp had lost many of his general business prospects. MORMON STEREOTYPING AND THE CRUSADE AGAINST POLYGAMY (1847-1896). Settlement in the West provided welcome isolation for the Church, but public disclosure of the practice of polygamy in 1852 brought a new barrage of ridicule and a confrontation with the federal government. The years from 1850 to 1890 were turbulent ones for the Church because reformers, ministers, and the press openly attacked the practice of polygamy. Opponents founded antipolygamy societies, and Congress passed antipolygamy legislation. Mormons were stereotyped as people who defied the law and were immoral. The clear aim of the judicial and political crusade against the Mormons was to destroy the Church. Only the 1890 manifesto, a statement by Church President Wilford Woodruff that abolished polygamy officially, pacified the government, allowing the return of confiscated Church property. Voluminous anti-Mormon writings, lectures, and cartoons at this time stereotyped the Church as a theocracy that defied the laws of conventional society; many portrayed its members as deluded and fanatical; and they alleged that polygamy, secret rituals, and blood Atonement were the theological underpinnings of the Church. The main motives were to discredit LDS belief, morally to reform a perceived evil, or to exploit the controversy for financial and political profit. The maligning tactics that were used included verbal attacks against Church leaders; caricatures in periodicals, magazines, and lectures; fictional inventions; and outright falsehoods. Probably the most influential anti-Mormon work in this period was Pomeroy Tucker's Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism (1867). A printer employed by E. B. Grandin, publisher of the Wayne Sentinel and printer of the first edition of the Book of Mormon, Tucker claimed to have been associated closely with Joseph Smith. He supported the Hurlbut-Howe charge that the Smiths were dishonest and alleged that they stole from their neighbors. However, he acknowledged that his insinuations were not "sustained by judicial investigation." The Reverend M. T. Lamb's The Golden Bible or the Book of Mormon: Is It from God? (1887) ridiculed the Book of Mormon as "verbose, blundering, stupid,…improbable,…impossible,…[and] a foolish guess." He described the book as unnecessary and far inferior to the Bible, and he characterized those who believe the Book of Mormon as being misinformed. Of fifty-six anti-Mormon novels published during the nineteenth century, four established a pattern for all of the others. The four were sensational, erotic novels focusing on the supposed plight of women in the Church. Alfreda Eva Bell's Boadicea, the Mormon Wife (1855) depicted Church members as "murderers, forgers, swindlers, gamblers, thieves, and adulterers!" Orvilla S. Belisle's Mormonism Unveiled (1855) had the heroine hopelessly trapped in a Mormon harem. Metta Victoria Fuller Victor's Mormon Wives (1856) characterized Mormons as a "horrid" and deluded people. Maria Ward (a pseudonym) depicted Mormon torture of women in Female Life Among the Mormons (1855). Authors wrote lurid passages designed to sell the publications. Excommunicated members tried to capitalize on their former membership in the Church to sell their stories. Fanny Stenhouse's Tell It All (1874) and Ann Eliza Young's Wife No. 19 (1876) sensationalized the polygamy theme. William Hickman sold his story to John H. Beadle, who exaggerated the danite myth in Brigham's Destroying Angel (1872) to caricature Mormons as a violent people. Church leaders responded to these attacks and adverse publicity only through sermons and admonitions. They defended the Church's fundamental doctrine of revelation and authority from God. During the period of federal prosecution, the First Presidency condemned the acts against the Church by the U.S. Congress and Supreme Court as violations of the United States Constitution. THE SEARCH FOR A PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATION (1897-1945). After the Church officially discontinued polygamy in 1890, the public image of Mormonism improved and became moderately favorable. However, in 1898 Utah elected to the U.S. Congress B. H. Roberts, who had entered into plural marriages before the Manifesto. His election revived polygamy charges and further exposés by magazine muckrakers, and Congress refused to seat him. During the congressional debate, the Order of Presbytery in Utah issued a publication, Ten Reasons Why Christians Cannot Fellowship the Mormon Church, mainly objecting to the doctrine of modern revelation. The election of Reed Smoot to the U.S. Senate (January 20, 1903) prompted additional controversy. Although he was not a polygamist, Smoot was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Ten months after he had been sworn in as a senator, his case was reviewed by the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections. The Smoot hearings lasted from January 1904 to February 1907. Finally, in 1907 the Senate voted to allow him to take his seat. The First Presidency then published An Address to the World, explaining the Church's doctrines and answering charges. The Salt Lake Ministerial Association rebutted that address in the Salt Lake Tribune on June 4, 1907. During 1910 and 1911, Pearson's, Collier's, Cosmopolitan, McClure's, and Everybody's magazines published vicious anti-Mormon articles. McClure's charged that the Mormons still practiced polygamy. Cosmopolitan compared Mormonism to a viper with tentacles reaching for wealth and power. The editors called the Church a "loathsome institution" whose "slimy grip" had served political and economic power in a dozen western states. These articles are classified by Church historians as the "magazine crusade." The advent of the motion picture brought a repetition of the anti-Mormon stereotype. From 1905 to 1936, at least twenty-one anti-Mormon films were produced. The most sordid of them were A Mormon Maid (1917) and Trapped by the Mormons (1922). The films depicted polygamous leaders seeking women converts to satisfy their lusts, and Mormons murdering innocent travelers in secret rites. Some of the most virulent anti-Mormon writings at this time came from Britain. Winifred Graham (Mrs. Theodore Cory), a professional anti-Mormon novelist, charged that Mormon missionaries were taking advantage of World War I by proselytizing women whose husbands were away to war. The film Trapped by the Mormons was based on one of her novels. When the Spaulding theory of Book of Mormon origins was discredited, anti-Mormon proponents turned to psychology to explain Joseph Smith's visions and revelations. Walter F. Prince and Theodore Schroeder offered explanations for Book of Mormon names by way of imaginative but remote psychological associations. I. Woodbridge Riley claimed in The Founder of Mormonism (New York, 1903) that "Joseph Smith, Junior was an epileptic." He was the first to suggest that Ethan Smith's View of the Hebrews (1823) and Josiah Priest's The Wonders of Nature and Providence, Displayed (1825) were the sources for the Book of Mormon. At the time the Church commemorated its centennial in 1930, American historian Bernard De Voto asserted in the American Mercury, "Unquestionably, Joseph Smith was a paranoid." He later admitted that the Mercury article was a "dishonest attack" (IE 49 [Mar. 1946]:154). Harry M. Beardsley, in Joseph Smith and His Mormon Empire (1931), advanced the theory that Joseph Smith's visions, revelations, and the Book of Mormon were by-products of his subconscious mind. Vardis Fisher, a popular novelist with Mormon roots in Idaho, published Children of God: An American Epic (1939). The work is somewhat sympathetic to the Mormon heritage, while offering a naturalistic origin for the Mormon practice of polygamy, and describes Joseph Smith in terms of "neurotic impulses." In 1945 Fawn Brodie published No Man Knows My History, a psychobiographical account of Joseph Smith. She portrayed him as a "prodigious mythmaker" who absorbed his theological ideas from his New York environment. The book repudiated the Rigdon-Spaulding theory, revived the Alexander Campbell thesis that Joseph Smith alone was the author of the book, and postulated that View of the Hebrews (following Riley, 1903) provided the basic source material for the Book of Mormon. Brodie's interpretations have been followed by several other writers. Church scholars have criticized Brodie's methods for several reasons. First, she ignored valuable manuscript material in the Church archives that was accessible to her. Second, her sources were mainly biased anti-Mormon documents collected primarily in the New York Public Library, Yale Library, and Chicago Historical Library. Third, she began with a predetermined conclusion that shaped her work: "I was convinced," she wrote, "before I ever began writing that Joseph Smith was not a true prophet," and felt compelled to supply an alternative explanation for his works (quoted in Newell G. Bringhurst, "Applause, Attack, and Ambivalence—Varied Responses to Fawn M. Brodie's No Man Knows My History," Utah Historical Quarterly 57 [Winter 1989]:47-48). Fourth, by using a psychobiographical approach, she imputed thoughts and motives to Joseph Smith. Even Vardis Fisher criticized her book, writing that it was "almost more a novel than a biography because she rarely hesitates to give the content of a mind or to explain motives which at best can only be surmised" (p. 57). REVIVAL OF OLD THEORIES AND ALLEGATIONS (1946-1990). Anti-Mormon writers were most prolific during the post-Brodie era. Despite a generally favorable press toward the Church during many of these years, of all anti-Mormon books, novels, pamphlets, tracts, and flyers published in English before 1990, more than half were published between 1960 and 1990 and a third of them between 1970 and 1990. Networks of anti-Mormon organizations operate in the United States. The 1987 Directory of Cult Research Organizations contains more than a hundred anti-Mormon listings. These networks distribute anti-Mormon literature, provide lectures that attack the Church publicly, and proselytize Mormons. Pacific Publishing House in California lists more than a hundred anti-Mormon publications. A broad spectrum of anti-Mormon authors has produced the invective literature of this period. Evangelicals and some apostate Mormons assert that Latter-day Saints are not Christians. The main basis for this judgment is that the Mormon belief in the Christian Godhead is different from the traditional Christian doctrine of the Trinity. They contend that Latter-day Saints worship a "different Jesus" and that their scriptures are contrary to the Bible. Another common tactic is to attempt to show how statements by past Church leaders contradict those by current leaders on such points as Adam as God, blood Atonement, and plural marriage. A current example of ridicule and distortion of Latter-day Saint beliefs comes from Edward Decker, an excommunicated Mormon and cofounder of Ex-Mormons for Jesus, now known as Saints Alive in Jesus. Professing love for the Saints, Decker has waged an attack on their beliefs. Latter-day Saints see his film and book, both entitled The Godmakers, as a gross misrepresentation of their beliefs, especially the temple ordinances. A regional director of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith and the Arizona Regional Board of the National Conference of Christians and Jews are among those who have condemned the film. Though anti-Mormon criticisms, misrepresentations, and falsehoods are offensive to Church members, the First Presidency has counseled members not to react to or debate those who sponsor them and has urged them to keep their responses "in the form of a positive explanation of the doctrines and practices of the Church" (Church News, Dec. 18, 1983, p. 2). Two prolific anti-Mormon researchers are Jerald and Sandra Tanner. They commenced writing in 1959 and now offer more than 200 publications. Their main approach is to demonstrate discrepancies, many of which Latter-day Saints consider contrived or trivial, between current and past Church teachings. They operate and publish under the name of the Utah Lighthouse Ministry, Inc. Their most notable work, Mormonism—Shadow or Reality? (1964, revised 1972, 1987), contains the essence of their claims against the Church. During the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, the Church had a generally favorable public image as reflected in the news media. That image became more negative in the later 1970s and the early 1980s. Church opposition to the equal rights amendment and the excommunication of Sonia Johnson for apostasy, the Church's position with respect to priesthood and blacks (changed in 1978), a First Presidency statement opposing the MX missile, the John Singer episode including the bombing of an LDS meetinghouse, tensions between some historians and Church leaders, the forged "Salamander" letter, and the other Mark Hofmann forgeries and murders have provided grist for negative press and television commentary. The political leverage of the Church and its financial holdings have also been subjects of articles with a strong negative orientation. A widely circulated anti-Mormon book, The Mormon Murders, by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith (1988), employs several strategies reminiscent of old-style anti-Semitism. The authors use the Hofmann forgeries and murders as a springboard and follow the stock anti-Mormon themes and methods found in earlier works. They explain Mormonism in terms of wealth, power, deception, and fear of the past. Church leaders have consistently appealed to the fairness of readers and urged them to examine the Book of Mormon and other latter-day scriptures and records for themselves rather than to prejudge the Church based on anti-Mormon publications. In 1972 the Church established the Public Communications Department, headquartered in Salt Lake City, to release public information about the Church. |