Anti-Polygamy Legislation |

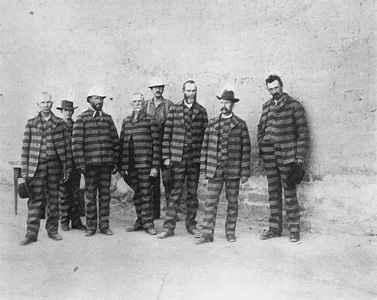

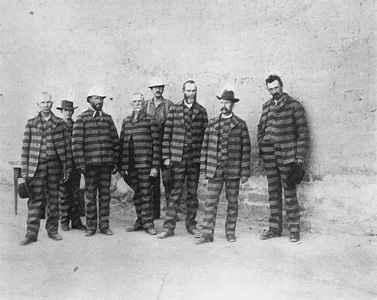

About 1,300 LDS men who had practiced plural marriage were jailed by federal officers pursuant to the Edmunds Act (1882), and many women were found "in contempt of court" and jailed for refusing to testify against their husbands. In the Utah penitentiary in 1885 are (from left to right) Francis A. Brown, Freddy Self, Moroni Brown, Amos Milton Musser, George H. Kellogg, Parley P. Pratt, Jr., Rudger Clawson, and Job Pingree. Photographer: John P. Soule.

by Ray Jay Davis

Bigamy is the crime of marrying while an undivorced spouse from a valid prior marriage is living. Because many prominent nineteenth-century Mormon men became polygamists under Church mandate, both their vulnerability to prosecution for bigamy and the legal attacks on the Church and its members for supporting plural marriage created a crisis for Mormonism during the 1870s and 1880s.

Bigamy was recognized as an offense by the early English ecclesiastical courts, which considered it an affront to the marriage Sacrament. Parliament enacted a statute in 1604 that made bigamy a felony cognizable in the English common law courts. After American independence, the states adopted antibigamy laws, but they received little attention until the nineteenth century in Utah.

The United States government has constitutional power to enact laws governing territories, and under that authority Congress enacted the Morrill Act (1862), making bigamy in a territory a crime punishable by a fine and five years in prison. The statute was upheld in Reynolds v. United States (1879), although the defendant argued that the law violated the First Amendment guarantee of the free exercise of religion.

Few Mormons were prosecuted for bigamy because the government had difficulty obtaining testimony about plural wedding ceremonies. Rather, they were charged with bigamous cohabitation, a misdemeanor created by the Edmunds Act (1882). Proving cohabitation was easy enough, and over 1,300 Latter-day Saints were jailed as "cohabs" in the 1880s.

Antipolygamy legislation also put pressure on the Church by threatening members' civil rights and Church property rights. The Edmunds Act barred persons living in polygamy from jury service, public office, and voting. The Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887) disincorporated both the Church and the Perpetual Emigrating Fund on the ground that they fostered polygamy. Furthermore, it authorized seizure of Church real estate not directly used for religious purposes, and acquired in excess of a $50,000 limitation imposed by the Morrill Act. In the Idaho Territory a test oath adopted in 1885 was used to ban all Mormons (and former Mormons) from voting because of the Church's position on polygamy.

In 1890 after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the seizure of Church property under the Edmunds-Tucker Act in The Late Corporation of the Mormon Church v. United States and the Idaho test oath in Davis v. Beason, it became clear that plural marriage was leading toward the economic and political destruction of the Church. Shortly after these decisions, a revelation was received by President Wilford Woodruff, who then withdrew the requirement for worthy males to take plural wives and announced the manifesto, formally stating his counsel to Latter-day Saints to abide by antibigamy laws (see D&C Official Declaration—1). The Manifesto ended the legal confrontation between the U.S. government and the Church.

Congress passed a final federal antibigamy provision in 1892, which excluded polygamists from immigration into the United States. This exclusion remains part of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Code.

Utah, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona incorporated antibigamy provisions into their turn-of-the-century state constitutions as required by Congress for admission to the Union. Idaho's Constitution not only outlaws bigamy but also bars polygamists and persons "celestially married" from public office and voting. However, that was interpreted in Budge v. Toncray by the Idaho court not to include monogamous Mormons married in an LDS temple.

During the twentieth century, federal and state governments have prosecuted other polygamists under a variety of general statutes. For example, federal officials have filed cases against polygamists charging unlawful use of the mails to proselytize for polygamy and alleging that moving plural wives across state boundaries violates laws against interstate kidnapping and interstate transportation of women for immoral purposes. Because of their practice of plural marriage, polygamists have also had legal troubles with state laws about adoption, inheritance, and government employment. Changing social attitudes about unconventional personal relationships may undermine the use of legislation in this way. For example, in 1988 an Arizona court held that it was illegal to deny a law enforcement security bond to an admitted polygamist merely because of his marital status.

Laws against plural marriage and its practitioners were enacted with reforming zeal. Congress and party platforms considered Mormon polygamy and southern slavery the "twin relics of barbarism." However, the lawmakers were not so forthcoming about their own religious bigotry: their aim was to destroy the Church's economic and political power, and bigamy was their tool. The Church's temporal position was eroded, but it survived the crisis.

(See Daily Living home page; Church History home page; Plural Marriage home page; Teachings About Marriage home page)

Bibliography

American Law Institute. Model Penal Code and Commentaries, Sec. 230.1. Philadelphia, 1980.

Davis, Ray Jay. "The Polygamous Prelude." American Journal of Legal History 6 (1962):1-27.

Driggs, Ken. "The Prosecutions Begin." Dialogue 21 (1988):109-125.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 1, Anti-Polygamy

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |